Tuesday, April 30, 2013

The RV FLIP

The RV FLIP is a research vessel that flips. Or bows, at least, since it only actually rotates about 90 degrees during normal operation. Still, the name (an acronym for FLoating Instrument Platform) is descriptive and evocative of what the ship does, and you can read more about it here:

RV FLIP

There are reasons (good) why FLIP is designed to do what she does. When her aft ballast tanks are flooded a 300-foot section of FLIP extends vertically below the ocean's surface, well below the influence of surface wave action. This provides FLIP with a steady platform ideal for the study of waves, acoustic properties of the ocean, and seawater conditions. In order to accommodate crews both underway and while moored, the interior of the ship is an Escher-esque labyrinth of doors in floors, toilets on walls, and converging staircases, which you can read more about on Winchell Chung's wonderful and time-consuming Atomic Rockets blog. As Mr. Chung points out there may be compelling reason to build spacecraft interiors this way, too. Pay attention to science, and you find design lessons in the oddest places.

Monday, April 29, 2013

Naked Mole Rat

Image source

The naked mole rat is a small social burrowing rodent native to the horn of Africa. Known mainly for being astonishingly ugly (Kim Possible cartoon version excepted), naked mole rats are remarkable little creatures, and you can read more about them here:

Naked mole rat

Growing up, one of my favorite skits I remember from Bill Nye the Science Guy is relevant to the current discussion:

Naked mole rats fit awkwardly into the typical classification scheme that defines what it is to be a mammal. In many ways, they behave more like giant ants with endoskeletons than like moles or rats. They're eusocial, forming large colonies with a single reproductive queen and many sterile female workers, have virtually no hair (hence the descriptor "naked"), and are content to let their body temperature rise and fall with their surroundings as though they're bucktoothed burrowing lizards. That said, their evolutionary lineage is clearly mammalian, so it's not as though there are any actual arguments on how to classify them.

For rodets, naked mole rats are built to last, reaching an age of up to 28 years, many times older than the oldest rats known. They also don't seem to process pain in the same way other mammals do, or at all really, and their nervous systems show no pain signalling when their skin is exposed to acid or capsaicin. It's thought that this is an adaptation to living in crowded burrows rich in carbon dioxide, which has a way of dropping the blood's pH. Most amazingly, cancer is unknown in naked mole rats, as their genomes appear to have a double-redundant mechanism to prevent cellular immortality. They might not be much to look at, but we clearly have a lot to learn from these little African beasts.

Of course, this discussion wouldn't be complete without the following video, my favorite by far in Zefrank1's True Facts series:

The naked mole rat is a small social burrowing rodent native to the horn of Africa. Known mainly for being astonishingly ugly (Kim Possible cartoon version excepted), naked mole rats are remarkable little creatures, and you can read more about them here:

Naked mole rat

Growing up, one of my favorite skits I remember from Bill Nye the Science Guy is relevant to the current discussion:

Naked mole rats fit awkwardly into the typical classification scheme that defines what it is to be a mammal. In many ways, they behave more like giant ants with endoskeletons than like moles or rats. They're eusocial, forming large colonies with a single reproductive queen and many sterile female workers, have virtually no hair (hence the descriptor "naked"), and are content to let their body temperature rise and fall with their surroundings as though they're bucktoothed burrowing lizards. That said, their evolutionary lineage is clearly mammalian, so it's not as though there are any actual arguments on how to classify them.

For rodets, naked mole rats are built to last, reaching an age of up to 28 years, many times older than the oldest rats known. They also don't seem to process pain in the same way other mammals do, or at all really, and their nervous systems show no pain signalling when their skin is exposed to acid or capsaicin. It's thought that this is an adaptation to living in crowded burrows rich in carbon dioxide, which has a way of dropping the blood's pH. Most amazingly, cancer is unknown in naked mole rats, as their genomes appear to have a double-redundant mechanism to prevent cellular immortality. They might not be much to look at, but we clearly have a lot to learn from these little African beasts.

Of course, this discussion wouldn't be complete without the following video, my favorite by far in Zefrank1's True Facts series:

Sunday, April 28, 2013

Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy

In 2010 a joint program led by NASA and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) began observing the sky with a 2.5-meter infrared telescope mounted in the aft fuselage of a modified Boeing 747SP. The program is known as the Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy or SOFIA (no relation to this blog, though I once worked with a guy who spent a summer internship working on the project), and you can read more about it here:

SOFIA

Infrared astronomy is difficult to conduct on Earth since the planet's ambient warmth and water vapor in the atmosphere tend to drown out much of the most interesting parts of the infrared band of the electromagnetic spectrum. One solution is to use space telescopes, such as the current Spitzer and the planned (and epically over-budget) James Webb Space Telescope. Observing from space eliminates the obscuring effects of Earth's temperature and atmosphere, but requires expensive design, assembly, and launch operations, and limits the practicality of upgrading the instrument once it's in service. Ground-based telescopes are much cheaper to build and get to, but lack the capability of their spaceborne counterparts. SOFIA sought to split the difference between these approaches by lifting the telescope to 45,000 feet, above most of the atmosphere, but retaining the ability to inspect and service the telescope each morning after SOFIA returns to her base at the Dryden Flight Research Center in the California desert.

The modifications carried out on the mothership to allow astronomy from the back of a 747 were not trivial, and this really is a remarkable, if relatively obscure program that NASA and the DLR are operating. Cutting a large section out of the fuselage does nasty aerodynamic things to the aircraft, inducing vibration that could potentially destroy the quality of any data obtained from the telescope. Evidently the engineers found a way around this, and they deserve great kudos for it.

The 747SP is a shortened, vaguely cartoonish-looking version of Boeing Commercial Airplanes' 1960s-vintage flagship. Originally intended to compete with the trijets offered by Lockheed and McDonnell Douglas, the 747's fuel burn was too high to be truly competitive with these smaller twin-aisle liners, and the 45 built proved more popular as airborne transonic luxury yachts for wealthy oil barons than long-haul money makers for the airlines. Doing science that once could only be done in space on the (relative) cheap goes a long way toward redeeming the airplane in my book.

Saturday, April 27, 2013

The Chernobyl Disaster

Image source

Early in the morning on April 26, 1986 a steam explosion blew the pressure dome off a 1.5-gigawatt nuclear reactor in the city of Pripyat, Ukraine. The release of fission products in the explosion and subsequent fire resulted in the worst civilian nuclear disaster in history, which you can read more about here:

The Chernobyl disaster

The events cascade that led to the Chernobyl disaster isn't really shocking because it happened, but because it was possible to happen. Every step of the causal chain, from the design of the reactor to the management of the plant to the Soviet Union's preparation for unplanned contingencies contributed to making things as bad as they were in the spring and summer of 1986 around Pripyat. Knowing this, I think it's silly to use the disaster as an argument against the use of nuclear energy, as some advocacy groups have done. Let's take a look at that chain to see whether the argument makes sense.

First, the design of the RBMK-1500 reactor that exploded was fundamentally flawed. At low power the reactor chugged along in fits and stops like an old rough-idling diesel engine. Spikes and dips in thermal output on the order of megawatts while idling were considered normal, and technicians had to proceed with extreme caution during low-power operations. At any power setting the reactor was designed with a positive void coefficient, meaning that if excess heat energy caused the coolant surrounding the fuel elements to begin to boil the reaction rate of the pile would increase, further increasing the rate of boiling. This is a runaway cycle requiring active control to prevent failure, and is unheard of in western reactors since it's entirely possible to design reactors with a negative void coefficient. On top of all this there was no adequate containment structure around the reactor. Any release of radioactive material from the reactor was designed to go straight into Pripyat's air supply, rather than be contained in an easily-quarantined concrete chamber.

Second, the immediate cause of the accident was a willingness to rush demonstration of an experimental procedure without adequate modelling and testing. The Chernobyl managers were concerned that in the event of a sudden reactor shutdown combined with a blackout on the electrical grid, it would take too long for a backup diesel generator to spool up and begin running the reactor's circulation pumps to keep the decaying uranium fuel from overheating. This is exactly the type of accident that occurred 25 years later at Fukushima, when a megathrust earthquake and tsunami simultaneously cut power to most of Japan's gird and destroyed the auxiliary power infrastructure at the plant. The plan was to scram the reaction in Chernobyl's reactor 4 but keep the steam generator running, using the tail-off of thermal power as the reaction halted to generate enough power to keep the turbines spinning and the circulation pumps running until the diesel generator come online. Had the procedure been followed as documented, things probably would've turned out fine. In the event, the reactor was inadvertently almost shut down early, and in their attempts to bring reactor 4's power back up to the prescribed level, technicians changed the initial conditions of the test, a massive power spike occurred, pressure built in the core faster than the unintended reaction could be stopped, and when the pressure exceeded the failure strength of the vessel it exploded in a flash phase change of the water coolant.

Had the reactor been sealed off from the outside world in a containment vessel, this still would've been bad, but not a disaster for the community. Due to the Chernobyl plant's design with no containment structure, the explosion ripped open a large section of the plant, allowing a plume of intensely radioactive smoke and ash generated by a fire in the graphite reactor moderator to escape into the surrounding environment. With no plan besides sending lots of people into a terrible place quickly, hundreds of emergency responders (later known as the liquidators) would be poisoned by the radiation, and many more workers and members of the surrounding communities will see cancer in their lives as a direct result of a few boneheaded design and management choices.

Remarkably, the disaster wasn't the end of the Chernobyl plant's operational life. Though a 30-kilometer radius around the plant has been evacuated of human inhabitation, and thus inadvertently become one of Europe's largest and most vibrant wildlife sanctuaries, once a sarcophagus was built to contain the remains of reactor 4 rotating shifts of workers came to Chernobyl to operate the remaining three reactors until its final decommissioning in 2000. As eager as Ukraine was to get the nightmarish history of Chernobyl and Pripyat behind it, people do like keeping the lights on.

Early in the morning on April 26, 1986 a steam explosion blew the pressure dome off a 1.5-gigawatt nuclear reactor in the city of Pripyat, Ukraine. The release of fission products in the explosion and subsequent fire resulted in the worst civilian nuclear disaster in history, which you can read more about here:

The Chernobyl disaster

The events cascade that led to the Chernobyl disaster isn't really shocking because it happened, but because it was possible to happen. Every step of the causal chain, from the design of the reactor to the management of the plant to the Soviet Union's preparation for unplanned contingencies contributed to making things as bad as they were in the spring and summer of 1986 around Pripyat. Knowing this, I think it's silly to use the disaster as an argument against the use of nuclear energy, as some advocacy groups have done. Let's take a look at that chain to see whether the argument makes sense.

First, the design of the RBMK-1500 reactor that exploded was fundamentally flawed. At low power the reactor chugged along in fits and stops like an old rough-idling diesel engine. Spikes and dips in thermal output on the order of megawatts while idling were considered normal, and technicians had to proceed with extreme caution during low-power operations. At any power setting the reactor was designed with a positive void coefficient, meaning that if excess heat energy caused the coolant surrounding the fuel elements to begin to boil the reaction rate of the pile would increase, further increasing the rate of boiling. This is a runaway cycle requiring active control to prevent failure, and is unheard of in western reactors since it's entirely possible to design reactors with a negative void coefficient. On top of all this there was no adequate containment structure around the reactor. Any release of radioactive material from the reactor was designed to go straight into Pripyat's air supply, rather than be contained in an easily-quarantined concrete chamber.

Second, the immediate cause of the accident was a willingness to rush demonstration of an experimental procedure without adequate modelling and testing. The Chernobyl managers were concerned that in the event of a sudden reactor shutdown combined with a blackout on the electrical grid, it would take too long for a backup diesel generator to spool up and begin running the reactor's circulation pumps to keep the decaying uranium fuel from overheating. This is exactly the type of accident that occurred 25 years later at Fukushima, when a megathrust earthquake and tsunami simultaneously cut power to most of Japan's gird and destroyed the auxiliary power infrastructure at the plant. The plan was to scram the reaction in Chernobyl's reactor 4 but keep the steam generator running, using the tail-off of thermal power as the reaction halted to generate enough power to keep the turbines spinning and the circulation pumps running until the diesel generator come online. Had the procedure been followed as documented, things probably would've turned out fine. In the event, the reactor was inadvertently almost shut down early, and in their attempts to bring reactor 4's power back up to the prescribed level, technicians changed the initial conditions of the test, a massive power spike occurred, pressure built in the core faster than the unintended reaction could be stopped, and when the pressure exceeded the failure strength of the vessel it exploded in a flash phase change of the water coolant.

Had the reactor been sealed off from the outside world in a containment vessel, this still would've been bad, but not a disaster for the community. Due to the Chernobyl plant's design with no containment structure, the explosion ripped open a large section of the plant, allowing a plume of intensely radioactive smoke and ash generated by a fire in the graphite reactor moderator to escape into the surrounding environment. With no plan besides sending lots of people into a terrible place quickly, hundreds of emergency responders (later known as the liquidators) would be poisoned by the radiation, and many more workers and members of the surrounding communities will see cancer in their lives as a direct result of a few boneheaded design and management choices.

Remarkably, the disaster wasn't the end of the Chernobyl plant's operational life. Though a 30-kilometer radius around the plant has been evacuated of human inhabitation, and thus inadvertently become one of Europe's largest and most vibrant wildlife sanctuaries, once a sarcophagus was built to contain the remains of reactor 4 rotating shifts of workers came to Chernobyl to operate the remaining three reactors until its final decommissioning in 2000. As eager as Ukraine was to get the nightmarish history of Chernobyl and Pripyat behind it, people do like keeping the lights on.

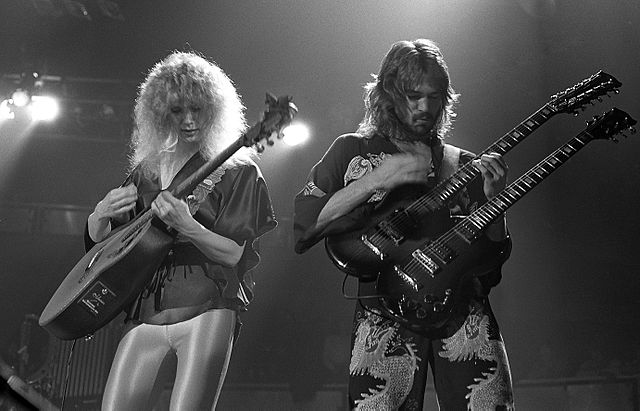

Friday, April 26, 2013

Heart

Last week, the metal and acoustic rock band Heart was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. This was a long time coming, as Heart is very good at what it does. You can read more about the band here:

Heart (not the organ this time)

Wikipedia lists 36 people who have been involved with Heart on stage over the years, but Ann and Nancy Wilson have formed the core of the band since they joined in the early 1970s. On the western shore of Green Lake, not far from my current apartment, the Wilson sisters saw a live performance of Led Zeppelin around the time people from Earth first walked on the Moon, and within a few years they set out to build the greatest tribute band to Led Zeppelin the world has ever seen. Need convincing? This song is a good starting point:

The studio processing helps with the psychedelic tone of much of Heart's work, but it's easier to appreciate Nancy's talent with the guitar in their live performances. Wilson's improvising is so effortless and charming it's clear she's a virtuoso who belongs with the likes of Page, Gilmour, and Richards among the greats of the classic rock canon:

Over the years Heart's lineup has changed quite a bit, and their style has wandered between hard rock, acoustic, and album-oriented rock. Truth be told I enjoy their early work most out of the band's discography. That said, the Wilson sisters have done some wonderful things relatively recently. Proof by selected example:

Clearly Heart is a close second only to Led Zeppelin at making wonderful music with Led Zeppelin's intellectual property.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Rotary Rocket

Image credit

In the late 1990s, engineer Gary Hudson led an effort to privately develop a manned single-stage reusable orbital launch vehicle for the bubbling LEO communications satellite market of the '90s. The company was called Rotary Rocket, did some spectacular things before it went under due to a lack of funding in 2001, and you can read more about it here:

Rotary Rocket

If you'd prefer the corporate propaganda version, you can find that here (give the video a minute to get rolling):

The last decade of the 20th Century was something of a fool's golden age for commercial spaceflight. Rotary Rocket was one of several start-up aerospace companies that soaked up tens (and sometimes hundreds) of millions of dollars before folding. At the time several spacecraft ventures, most notably Iridium, seriously planned constellations of hundreds of satellites to enable global high-speed broadband communication. Keep in mind that this was the same decade that was bookended by the collapse of the Soviet Union and 9/11, when the media couldn't think of anything better to cover than El Nino and the sex life of the American president. People weren't really thinking straight during that whole decade, and the comsat bubble was just one symptom.

The thinking at the time was that hundreds of satellites were going to need a ride to low Earth orbit fast, and it simply wouldn't be economical to launch them on expendable rockets that charge north of $10,000 per pound to orbit. The great scandal of the space industry is that this cost is driven almost entirely by low launch rates and the cost of the vehicle that's dumped into the ocean after each flight, and though the technology has existed for decades to enable high-cadence low-cost reusable flight to LEO, no one has been willing to invest the capital to mature this technology into an operational system. Impatient at the pace of the government space agencies and legacy contractors, the start-ups sought to change this.

Rotary Rocket set out to accomplish an extremely difficult feat with nowhere near enough cash to finish the job. While the concept of a single rocket stage flying to orbit, delivering payload, and returning to Earth for refueling and relaunch soon after is simple enough, the vagaries of physics make such a vehicle almost impossible to design or build. Such a machine needs to be more than 90% propellant on launch, with structure, engines, payload, guidance and control systems, recovery gear, and (in the case of Rotary's Roton vehicle) crew accommodations stuffed into just a few percent of the initial launch mass. Hitting this mass target requires every technological and engineering trick imaginable, and even then there's debate over whether it can actually be done. Still, Rotary tried. You have to admit, what they lacked in funds they more than made up for with guts.

The most interesting feature of Rotary's rocket was its recovery system, from which the company derived its name. Rather than glide to a runway with wings, parachute like a capsule, or rocket to a screeching halt Buck Rogers-style, Rotary planned to use a set of deployable rotor blades powered by miniature hydrogen peroxide-propelled rocket at their tips to slow the vehicle to a gentle, precise decent to a helipad. Does this strategy really make sense? Rotary claimed it granted their rocket a significant recovery mass reduction relative to wings, but the fact that no one else in a highly speculative industry has had much to say on the concept suggests that it was as much a marketing gimmick as a physics strategy.

Still, it afforded the company an opportunity for some jaw-dropping photo opportunities. Working with what they had, Hudson et. al. built a full-scale replica of the Roton to simulate the last phase of descending flight. Flying this test vehicle could best be described as "challenging." The pilot-friendliness of flying machines is quantified by the Cooper-Harper scale, with a 1 representing excellent controllability at all times and 10 meaning that control loss is inevitable during operation. Every pilot who flew the Roton simulation rated it a perfectly awful 10, but still, flight is exactly what Roton did:

Brian Binnie, who co-piloted each flight of the Roton test vehicle, would earn his gold astronaut wings five years later while at Scaled Composites, when he piloted SpaceShipOne beyond the edge of the atmosphere for its triumphant X Prize winning flight. Much of the Rotary Rocket team is still working, their intellectual property alive elsewhere in the NewSpace industry. It's a shame things didn't work out for Rotary, but at least they gave the problem a decent shot.

In the late 1990s, engineer Gary Hudson led an effort to privately develop a manned single-stage reusable orbital launch vehicle for the bubbling LEO communications satellite market of the '90s. The company was called Rotary Rocket, did some spectacular things before it went under due to a lack of funding in 2001, and you can read more about it here:

Rotary Rocket

If you'd prefer the corporate propaganda version, you can find that here (give the video a minute to get rolling):

The last decade of the 20th Century was something of a fool's golden age for commercial spaceflight. Rotary Rocket was one of several start-up aerospace companies that soaked up tens (and sometimes hundreds) of millions of dollars before folding. At the time several spacecraft ventures, most notably Iridium, seriously planned constellations of hundreds of satellites to enable global high-speed broadband communication. Keep in mind that this was the same decade that was bookended by the collapse of the Soviet Union and 9/11, when the media couldn't think of anything better to cover than El Nino and the sex life of the American president. People weren't really thinking straight during that whole decade, and the comsat bubble was just one symptom.

The thinking at the time was that hundreds of satellites were going to need a ride to low Earth orbit fast, and it simply wouldn't be economical to launch them on expendable rockets that charge north of $10,000 per pound to orbit. The great scandal of the space industry is that this cost is driven almost entirely by low launch rates and the cost of the vehicle that's dumped into the ocean after each flight, and though the technology has existed for decades to enable high-cadence low-cost reusable flight to LEO, no one has been willing to invest the capital to mature this technology into an operational system. Impatient at the pace of the government space agencies and legacy contractors, the start-ups sought to change this.

Rotary Rocket set out to accomplish an extremely difficult feat with nowhere near enough cash to finish the job. While the concept of a single rocket stage flying to orbit, delivering payload, and returning to Earth for refueling and relaunch soon after is simple enough, the vagaries of physics make such a vehicle almost impossible to design or build. Such a machine needs to be more than 90% propellant on launch, with structure, engines, payload, guidance and control systems, recovery gear, and (in the case of Rotary's Roton vehicle) crew accommodations stuffed into just a few percent of the initial launch mass. Hitting this mass target requires every technological and engineering trick imaginable, and even then there's debate over whether it can actually be done. Still, Rotary tried. You have to admit, what they lacked in funds they more than made up for with guts.

The most interesting feature of Rotary's rocket was its recovery system, from which the company derived its name. Rather than glide to a runway with wings, parachute like a capsule, or rocket to a screeching halt Buck Rogers-style, Rotary planned to use a set of deployable rotor blades powered by miniature hydrogen peroxide-propelled rocket at their tips to slow the vehicle to a gentle, precise decent to a helipad. Does this strategy really make sense? Rotary claimed it granted their rocket a significant recovery mass reduction relative to wings, but the fact that no one else in a highly speculative industry has had much to say on the concept suggests that it was as much a marketing gimmick as a physics strategy.

Still, it afforded the company an opportunity for some jaw-dropping photo opportunities. Working with what they had, Hudson et. al. built a full-scale replica of the Roton to simulate the last phase of descending flight. Flying this test vehicle could best be described as "challenging." The pilot-friendliness of flying machines is quantified by the Cooper-Harper scale, with a 1 representing excellent controllability at all times and 10 meaning that control loss is inevitable during operation. Every pilot who flew the Roton simulation rated it a perfectly awful 10, but still, flight is exactly what Roton did:

Brian Binnie, who co-piloted each flight of the Roton test vehicle, would earn his gold astronaut wings five years later while at Scaled Composites, when he piloted SpaceShipOne beyond the edge of the atmosphere for its triumphant X Prize winning flight. Much of the Rotary Rocket team is still working, their intellectual property alive elsewhere in the NewSpace industry. It's a shame things didn't work out for Rotary, but at least they gave the problem a decent shot.

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Alcohol Laws of New Jersey

Image credit

The state of New Jersey has some of the most complicated laws dealing with the production, distribution, sale, and consumption of ethanol in the United States. You can read more about them here:

Alcohol laws of New Jersey

New Jersey is a very old state; only Delaware and Pennsylvania entered the union before it. This isn't really an excuse for the hideous complexity of alcohol laws in the Garden State, but it works a little bit better as an explanation. Older governments tend to become palimpsests of regulations on laws on constitutions re-jiggered into rules that may or may not actually be enforced. Still, the patchwork quilt of legal frameworks that runs from the Atlantic coast to the Delaware River gives me a bit of headache, and seems to be asking for replacement with something more sensible.

It makes sense that things like landing gear, the stock market, and the human genome are complex, though each's complexity emerges in its own way from simple beginnings. New Jersey's alcohol laws, though. There's just no excuse for that.

The state of New Jersey has some of the most complicated laws dealing with the production, distribution, sale, and consumption of ethanol in the United States. You can read more about them here:

Alcohol laws of New Jersey

New Jersey is a very old state; only Delaware and Pennsylvania entered the union before it. This isn't really an excuse for the hideous complexity of alcohol laws in the Garden State, but it works a little bit better as an explanation. Older governments tend to become palimpsests of regulations on laws on constitutions re-jiggered into rules that may or may not actually be enforced. Still, the patchwork quilt of legal frameworks that runs from the Atlantic coast to the Delaware River gives me a bit of headache, and seems to be asking for replacement with something more sensible.

It makes sense that things like landing gear, the stock market, and the human genome are complex, though each's complexity emerges in its own way from simple beginnings. New Jersey's alcohol laws, though. There's just no excuse for that.

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

List of Fictional Books

Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia famous among teachers as an unacceptable reference and among students as an introductory source on nearly all knowledge thus far acquired by humans, maintains a surprisingly authoritative list of books that don't actually exist. You can take a look at the list here:

List of fictional books

Note that the list is not concerned with works of fiction so much as it is with works that exist only in the prose of writers of fiction. I say that Wikipedia's list is surprising, but those who are familiar with the site shouldn't be surprised at all. The flagship of the Wikimedia Foundation is well-curated, with over four million articles in English and a large pack of editors who zealously and expeditiously smite even reasonable minor edits to articles when they don't come from an acceptable source. Thousands of people at least have contributed to Wikipedia's list of books that don't exist in this universe, and the list extends to a dizzying height.

Since I don't have very much clever to say about fictional books, here's a video of Carl Sagan talking about books that do exist:

Monday, April 22, 2013

"When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer"

One of the poems in Walt Whitman's 1855 anthology Leaves of Grass describes the tension between scientific explanation and direct experience through the lens of astronomy and observation. Describing poetry is generally useless, so you're much better off reading the poem here:

"When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer"

I have mixed feelings about Walt Whitman. As someone who falls in love easily with places and nature, I identify most of the way with his romanticism, but there always seemed to be an unfortunate undercurrent of anti-intellectualism in his work to me. That said, "When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer" makes perfect sense to me after a year in the murky depths of graduate school. It's easy to measure quantitative things, and the academic world is merciless in reducing everything within reach into a pile of numbers to be chewed up for breakfast in the latest numerical simulation. The numbers, the charts, the figures, and the proofs all mean something, and with any luck it actually corresponds to something in the real world, but it's nice to get out and actually enjoy that mystical moist night air in perfect silence every once in a while.

Sunday, April 21, 2013

The Battle of San Jacinto

The decisive battle in Texas's fight for independence from Mexico was fought 177 years ago today, on April 21, 1836. Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna's forces were decisively routed during the 18-minute-long battle in the coastal plains just south of present-day Houston, and the victorious conclusion for the Texans would have profound repercussions on the current border of the United States and Mexico. You can read more about it here:

Battle of San Jacinto

Not being a native Texan, I didn't hear the great founding stories and creation myths of Texas during my youth, but Texans will be happy to tell you all about these stories if you just stop and wait for a while among the bluebonnets and longhorn cattle. The history of the Battle of San Jacinto is full of both exciting narrative (Sam Houston's rallying cry of "Remember the Alamo!") and myth (the story of Emily Morgan, which probably didn't really happen but inspired the song "The Yellow Rose of Texas" anyway). Over the years oil refineries and chemical plants have sprouted like dandelions in the Harris County lowlands, and it's hard to tell where the battle was fought today. Ever helpful to tourists, the Texans saw fit to erect a 570 foot monument near the battle site, which might be the world's largest historical marker. My only experience there was in the thick of Houston summer, the air sweltering with humidity and alive with mosquitoes. If you visit, I suggest picking a month other than July.

Saturday, April 20, 2013

Washington Initiative 502

On November 6, 2012, the state of Washington began a government-backed program of civil disobedience against federal drug law by legalizing the recreational use of marijuana in the state. This began with the passage of voter initiative 502, which you can read more about here:

Washington Initiative 502

What's most striking to me about I-502 is how broad the base of support for the initiative was. Sponsors included US attorneys, city attorneys, state representatives, health officials, and two past presidents of the Washington State Bar Association. I-502 was a voter initiative, not a piece of legislative action, but clearly it had much support in the mainstream political arena. I suspect republicans and democrats voted for it in large numbers, whether out of a philosophical defense of liberty or a pragmatic desire to devote law enforcement resources to more meaningful things.

Whatever the rationale, no one who works for the state of Washington will get in the way of a (private) 4/20 celebration, though its still on the books as a violation of the federal controlled substances act. Presumably the feds have better things to do than rustling anyone's jimmies on this issue. That's what Olympia is counting on, anyway.

Friday, April 19, 2013

History of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide

LSD was first synthesized in 1938, and in the 75 years since then the chemical has had a profoundly turbulent and influential history. The domains of psychology, theory of mind, public policy, and creative expression have all been deeply touched by the influence of the gold standard of the psychedelics, in a way that's not taught or known as widely as I'd like. You can read more about that history here:

History of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

First, a largely irrelevant comment on notation. "LSD" is an initialism for the German "Lysergsäure-diethylamid." Since initialisms don't translate, this one seems a bit nonsensical in English. Had LSD been discovered in the United States, it would probably be known as "LAD" today, but that's just not the particular universe we live in. Sandoz Laboratories, the original patent-holder on LSD, marketed it under the brand name Delysid, and if you want to sound streetwise you can call it "acid" or "Lucy." Back to history.

Bicycle day, April 19, 1943, is one of the most important days in the history of LSD. Albert Hofmann first synthesized the derivative compound of the ergot fungus five years earlier, and accidentally dosed himself for the first time three days before bicycle day, but wanting to further understand and characterize the phenomenological properties of LSD, he self-administered the first intentional dose of the psychedelic three days later. Hofmann did a back-of-the-envelope calculation to estimate the smallest possible dose that could induce any psychedelic effects, and came up with 250 micrograms. This is about two and a half times a typical street dose and an order of magnitude over the threshold dosage. Hofmann didn't know it at the time, but he was in for a very unusual day.

Fortunately LSD is virtually harmless from a physiological point of view, and its ratio of lethal to threshold dosage is greater than that of caffeine. Within an hour, the Sandoz chemist began experiencing hallucinations, synesthesia, and an intensely different perception of time and space. Since vehicles were restricted in wartime Switzerland, he rode his bike home in what must have been one of the weirdest bike rides in human history, went through periods of severe anxiety, determined that he was safe after a while, and enjoyed the intense magnification and distortion of human perception under psychedelic consciousness until the drug wore off.

This was only the beginning, of course. Sandoz knew it had a powerful technology on its hands, but didn't know what to do with it. Extensive scientific research was conducted in the 1950s and early '60s on psychedelic therapy. Psychology students were offered free doses in an attempt to better understand psychosis. Mainstream psychologists administered Delysid to their patients as therapy for addiction, anxiety, and depression. Before LSD, drugs were not thought to be a viable option for treating depression. Since this research, drugs (particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) have become one of the most important arrows in psychiatry's quiver. The CIA and NATO forces sought to weaponize the drug, predictably leading to some unfortunate consequences and at least one hilarious video of British troops traipsing about the forest on acid. For science:

Attempting to use a technology better suited to peaceful exploration and healing for war didn't help, but in the end it was Timothy Leary's irrational exuberance for LSD that most directly led to its ejection from the mainstream. President Nixon labelled Leary "the most dangerous man in America" for his promotion of the counterculture and his association of psychedelics with it. Meanwhile Nixon authorized the bombing of Cambodia and cancelled lunar exploration after Apollo 17. Funny how those labels sort themselves out.

The psychedelics, foremost among them LSD, stayed influential even after they went on the DEA's list of controlled substances and the black market. The exact effects are just more difficult to determine now. What we do know is that the work of musicians from The Beatles to Animal Collective has been strongly influenced by psychedelic experience (and M83 has composed at least one thinly-veiled advertisment for LSD), as have the careers of people like Steve Jobs and Kary Mullis. Technology builds on technology, and it's hard to quantify the value of new perspective in the creative process. Suffice it to say that Hofmann's potion has affected more of the previous and current centuries than you might think, and the effect might be more positive than you imagine.

After decades of marginalization from the scientific sphere, meaningful clinical trials using psychedelics (and sometimes LSD) to treat end-of-life anxiety, cluster headaches, and PTSD are ramping up. Hopefully the sociological lesson has been learned, and the researchers will be more cautiously optimistic than irrationally exuberant. It's time to stop the madness against a tool that has tremendous potential for discovery and therapy. With any luck, there's much joyful history to be added to the Wikipedia article in the future.

I'm off my soapbox, but here's one last thing before I go. The following video, from the first golden age of psychedelic research. Why? Because it's my blog and I can link to Youtube videos of pretty British girls on acid if I want to:

I gotta admit, the end is a bit silly. Sorry about that.

Thursday, April 18, 2013

The Doolittle Raid

The first American air raid on the Japanese home islands during World War II was launched on April 18, 1942, four months after the opening Japanese attack on US forces in the Philippines, Guam, Wake Island, and Oahu. The raid was tactically insignificant, carried out by only 16 North American B-25 bombers, all of which were lost in the raid, but was a tremendous psychological victory for the United States in the Pacific theater. You can read more about it here:

The Doolittle Raid

Since the United States had no air bases within striking distance of Japan given the range of aircraft available at the time, the B-25's were moved into position and launched off the aircraft carrier USS Hornet 650 nautical miles from the island of Honshu. The bombers were just barely able to take off in the space of the Hornet's deck, and since they weren't equipped to land on the carrier, the plan was to fly on to airfields in unoccupied nationalist China, from which presumably the crews and aircraft would be returned to America. When a Japanese picket boat spotted the Hornet 10 hours before the scheduled launch time, the decision was made to fly immediately, and as a result none of the B-25s had sufficient fuel to reach their intended destinations. Only one airplane landed on a runway, in Vladivostok, where the crew was interred by the Soviet Union for a year and the airplane became a jungle gym for elementary school kids.

Remarkably, 73 of the 80 Doolittle raiders made it back to the United States, where Jimmy Doolittle, leader and chief planner of the raid, was convinced he would be court-martialed for the loss of a squadron of bombers with little to show for it. In the event, America went wild for Doolittle and his airmen, branded them heroes of the first order, and granted Doolittle a Medal of Honor and ultimately a promotion to General. Given the complexity and foolhardiness of the raid, this is about as well as things could have been expected to go.

Wednesday, April 17, 2013

Scotoplanes

Image credit

Scotoplanes, known more whimsically and pronounceably as the sea pig, is a genus of deep water sea cucumbers that reside on the abyssal plains of the world's oceans. Unlike most sea cucumbers, sea pigs use a set of enlarged tube feet to scuttle about the ocean floor, and prefer walking to swimming. I'm assuming creatures without brains have preferences, which may not strictly speaking be the case. The Wikipedia article on the sea pig is rather terse, but let's be honest, the real reason I'm writing this is as an excuse to post this video, which is one of the best things I've seen on the internet in recent memory:

This is a teachable moment on technical language. A cloaca and an anus are not the same thing, so statements like "the sea pig breathes through its anus" aren't really correct. The narrator makes this distinction one time, then proceeds to completely ignore it during the rest of the video. It's for comedic effect, and I sympathize with that, but it's still not right. Words mean things. An explosion is not the same thing as a fire or a rapid unscheduled disassembly (RUD), weight is not the same thing as mass, and a motor is not the same kind of thing as an engine. Playing fast and loose with well-specified language often still gets the point across, but is a dangerous game in the land of science and engineering. More on that later.

Did I really just spend a paragraph complaining (mostly) about why people should be careful about when they use the word "explosion?" Engineering school has ruined me forever. Enjoy learning facts about the sea pig. Any of them, really, it doesn't much matter which one.

Scotoplanes, known more whimsically and pronounceably as the sea pig, is a genus of deep water sea cucumbers that reside on the abyssal plains of the world's oceans. Unlike most sea cucumbers, sea pigs use a set of enlarged tube feet to scuttle about the ocean floor, and prefer walking to swimming. I'm assuming creatures without brains have preferences, which may not strictly speaking be the case. The Wikipedia article on the sea pig is rather terse, but let's be honest, the real reason I'm writing this is as an excuse to post this video, which is one of the best things I've seen on the internet in recent memory:

This is a teachable moment on technical language. A cloaca and an anus are not the same thing, so statements like "the sea pig breathes through its anus" aren't really correct. The narrator makes this distinction one time, then proceeds to completely ignore it during the rest of the video. It's for comedic effect, and I sympathize with that, but it's still not right. Words mean things. An explosion is not the same thing as a fire or a rapid unscheduled disassembly (RUD), weight is not the same thing as mass, and a motor is not the same kind of thing as an engine. Playing fast and loose with well-specified language often still gets the point across, but is a dangerous game in the land of science and engineering. More on that later.

Did I really just spend a paragraph complaining (mostly) about why people should be careful about when they use the word "explosion?" Engineering school has ruined me forever. Enjoy learning facts about the sea pig. Any of them, really, it doesn't much matter which one.

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

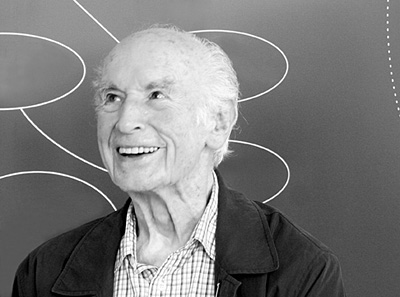

Albert Hofmann

Albert Hofmann was a Swiss biochemist who authored over 100 scientific papers and several books during his career. He is best known for discovering and characterizing the psychedelic properties of the semisynthetic tryptamine lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), but Dr. Hofmann was also the first person to scientifically describe psilocybin and psilocin, the active ingredients in psychedelic mushrooms, and many other compounds, psychoactive and otherwise, during his career. You can read more about him here:

Albert Hofmann

Hofmann's career was promising but not extraordinary until 70 years ago today, when he accidentally exposed himself to about a few dozen micrograms of LSD while researching derivative compounds of lysergic acid at Sandoz Laboratories in Basel. Though Hofmann first synthesized LSD five years previously, the tryptamine seemed of little interest until that spring day in 1943. The quantity of chemical he ingested was minuscule, about the size of a mote of dust, but fortunately for Hofmann and the psychonauts who followed after him (a distinguished group that includes people like Aldous Huxley, Francis Crick, and the inventor of the polymerase chain reaction process), LSD is shockingly potent. Within an hour of exposure, his imagination lit up with the kaleidoscopic imagery and synesthesia of psychedelic consciousness, and like the scientist he was, Hofmann quickly put together the root cause and sought to understand it.

The discovery of April 1943 would shape much of the rest of Hofmann's career in chemistry. Eventually he found that the curious effect of LSD on the mind stemmed from stimulating action on the brain's 5-HT2A receptors, and Hofmann characterized a wide variety of other selective serotonin receptor agonists over the next five decades. Hofmann was a talented communicator as well, and throughout the second half of his long life he spoke out against the irresponsibility of the counterculture and the CIA, and in favor of the many practical applications of psychedelics. As Korolyov and Von Braun led the exploration of the cosmos during the 20th Century, so Hofmann took the reigns of the exploration of altered consciousness.

The Wikipedia article on Hofmann is wonderful in part because much of it quotes directly from its subject. Here's Dr. Hofmann on how he came to decide on a career in chemistry:

"This [career] decision was not easy for me. I had already taken a Latin matricular exam, and therefore a career in the humanities stood out most prominently in the foreground. Moreover, an artistic career was tempting. In the end, however, it was a problem of theoretical knowledge which induced me to study chemistry, which was a great surprise to all who knew me. Mystical experiences in childhood, in which Nature was altered in magical ways, had provoked questions concerning the essence of the external, material world, and chemistry was the scientific field which might afford insights into this."

To Hofmann, the mystical and the scientific were intimately correlated, and he never saw fit to disparage either type of experience. Clearly this was a man after my own heart. On the day he turned 100 years old, reflecting on a long, surprising, and wonderful trek of discovery, Albert Hofmann had this to say about the future of the chemical he referred to as his problem child in his later years:

"It gave me an inner joy, an open mindedness, a gratefulness, open eyes and an internal sensitivity for the miracles of creation. [...] I think that in human evolution it has never been as necessary to have this substance LSD. It is just a tool to turn us into what we are supposed to be."

It's a shame that Albert Hofmann never earned a Nobel Prize for his century of contributions to science and our understanding of the mind's place in the cosmos. I think the future will look more kindly upon him than the present does.

Monday, April 15, 2013

The SS Californian

Just after midnight on April 15, 1912, once it became clear that the RMS Titanic was bound shortly for the bottom of the Atlantic, her officers tried to signal a ship about 10 miles away, seeking her assistance in offloading their passengers to a safe rescue. While that ship, the merchant steamer SS Californian, did other things during her war-truncated 14 year career, literally falling asleep at the helm while the Titanic sank will forever be her most memorable legacy. You can read more about the ship here:

The SS Californian

The Californian was a smaller and slower ship than the Titanic, and when captain Stanley Lord made the decision to stop for the night rather than risk crossing a dense ice field in moonless darkness, radio operator Cyril Evans saw no reason to stay up late. Around 11:30 he attempted to warn the Titanic, then racing at full speed deeper into the Labrador Current, about the dangerous ice ahead, and was greeted by this response from the big liner: "Shut up, shut up! I am busy; I am working Cape Race!" Ten minutes later Titanic would come to a wounded halt after ripping open too many watertight compartments to stay afloat on an iceberg. Sometimes timing and politeness, or lack thereof, is everything.

Would lives have been saved if Evans had stayed up a little bit longer and heard the initial "SOS" from Titanic? Certainly, but it's hard to imagine things ending well. Titanic was carrying a small town's worth of people, well over 2,000, and by the time Californian would've arrived at the site, Titanic would only have had another hour or so left to go on the surface, probably not enough time to transfer everyone over. By the time the Titanic's officers launched flares in an attempt to rouse the attention of those on the Californian, it was probably already too late to make a difference. Still, the facts are maddening, and it seems like the Californian should've done something to help, however ineffective it might have wound up being.

Three years later, this littler ship would join her bigger cousin below the ocean waves, this time some distance west of the island of Crete. World War I was an awful, violent time, and the Californian was jut another victim. Her life was shorter and more tragic than it should've been, but at least these kinds of accidents and sinkings don't happen often any more.

Friday, April 12, 2013

Yuri Gagarin

Image source

As of this writing 530 people have traveled in space. The first of these flew for the first time 52 years ago today, and you can read more about him here:

Yuri Gagarin

One of the interesting things about Yuri Gagarin was the relative ordinariness of his life until he boarded the Vostok 1 capsule in 1961. He studied tractors in vocational school, was recommended for pilot training after being drafted into the Red Army, and was selected among the first group of novice Air Force pilots groomed for spaceflight by Sergei Korolyov, the Soviet space program's chief designer. The narratives of exploration are filled with people who doggedly and often bone-headedly followed the call of the wild in the face of opposition. Columbus, Amundsen, the Wrights, Goddard, Mallory, and Lindbergh all pursued their targets as solo ventures, or by campaigning vigorously for support. By contrast, Gagarin was chosen by the big Soviet machine to be first. He no more campaigned for his part in the drama than he campaigned to become premier of the Soviet Union.

This is not to speak ill of his skills as a pilot, cosmonaut, or explorer in any way. The story of Gagarin and his selection to fly Vostok 1 just shows how much the technological game changed during the last century. Technological development has always been a collaborative enterprise, but this is more true now than ever before. One way or another, Gagarin was a good personified symbol of the progress humanity's made in recent times, and it's a shame that his life ended far too young on a training flight just seven years after his historic first step into the cosmos. Were he around today, I cant imagine a better ambassador for spaceflight's place in the public consciousness.

Happy Yuri's Night, everybody, and poyekhali!

As of this writing 530 people have traveled in space. The first of these flew for the first time 52 years ago today, and you can read more about him here:

Yuri Gagarin

One of the interesting things about Yuri Gagarin was the relative ordinariness of his life until he boarded the Vostok 1 capsule in 1961. He studied tractors in vocational school, was recommended for pilot training after being drafted into the Red Army, and was selected among the first group of novice Air Force pilots groomed for spaceflight by Sergei Korolyov, the Soviet space program's chief designer. The narratives of exploration are filled with people who doggedly and often bone-headedly followed the call of the wild in the face of opposition. Columbus, Amundsen, the Wrights, Goddard, Mallory, and Lindbergh all pursued their targets as solo ventures, or by campaigning vigorously for support. By contrast, Gagarin was chosen by the big Soviet machine to be first. He no more campaigned for his part in the drama than he campaigned to become premier of the Soviet Union.

This is not to speak ill of his skills as a pilot, cosmonaut, or explorer in any way. The story of Gagarin and his selection to fly Vostok 1 just shows how much the technological game changed during the last century. Technological development has always been a collaborative enterprise, but this is more true now than ever before. One way or another, Gagarin was a good personified symbol of the progress humanity's made in recent times, and it's a shame that his life ended far too young on a training flight just seven years after his historic first step into the cosmos. Were he around today, I cant imagine a better ambassador for spaceflight's place in the public consciousness.

Happy Yuri's Night, everybody, and poyekhali!

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Neutron Star

When stars evolve off the main sequence, the physics of gravity overpowers whatever nuclear exhaust is left, and stars of all sizes ultimately collapse into exotic physical forms. The middle children of the stellar population, those to large to become white dwarfs and too small to rip the fabric of spacetime apart and become black holes, become neutron stars. You can read more about these end-stage stars here:

Neutron star

I don't mean to sound like a hipster, but this is more mainstream than most of the topics I write about in this space. Why talk about something we read about in a high school science textbook? While I assume that most people with a background in science have some passing understanding of what neutron stars are, the details are more esoteric, and were new to me until I wound up derping around on the Wikipedia page earlier today. It's interesting to see how strange life becomes when gravity's volume is turned up to 11.

Gravity is by far the weakest of the fundamental forces of physical law. The nuclear forces bind protons and neutrons together in a vice grip that can't be broken until temperatures in the millions of degrees, and a few ounces of steel can easily defeat all the Earth's gravity in a tug-of-war when a magnet sticks to the fridge. In all the places people go gravity's call is pound for pound nothing but a whisper. Inside a neutron star, though, where the mass of half a million Earths is compressed into the size of a thunderhead, the tug is enough to slow the passage of time and create a layer cake of wonderland flavors of matter.

Not convinced that the inside of a neutron star is an exotically exciting place? Consider for a moment that the best diagram we can draw of such a place, based on the combined observations and theoretical development of a century in astronomy, particle physics, and relativity, has a question mark right in the bull's-eye:

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Gough Island

Image credit

The most remote patch of land on Earth is the Tristan da Cunha archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean. Of these islands, Tristan da Cunha is the only one that's truly inhabited with a real sense of community, but smaller Gough Island, 400 kilometers southeast of its archipelago partners, boasts a weather station permanently staffed by a crew of 6. In a sense this station could be considered the most isolated permanent human presence after the International Space Station. You can read more about the island, its history, and the station here:

Gough Island

The Wikipedia article is informative and interesting, but its this gallery that really motivated me to make this post. Learning about remote and esoteric places is a hobby of mine, and I have fun collecting facts about tiny islands in faraway seas the way some people have fun collecting stamps or bottle caps. Seeing galleries like Chantal Steyn's elevate this to a whole new level, though, and make it clear how charged with wonder the universe really is. Out of thousands of miles of trackless ocean, far from the bustling harbors of Africa and South America and even from the glaciered shores of Antarctica, the powers that made the Earth saw fit to lift a tiny patch rock above the waves, and the result is simple, jaw-dropping beauty in every direction. What a world we live in.

The most remote patch of land on Earth is the Tristan da Cunha archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean. Of these islands, Tristan da Cunha is the only one that's truly inhabited with a real sense of community, but smaller Gough Island, 400 kilometers southeast of its archipelago partners, boasts a weather station permanently staffed by a crew of 6. In a sense this station could be considered the most isolated permanent human presence after the International Space Station. You can read more about the island, its history, and the station here:

Gough Island

The Wikipedia article is informative and interesting, but its this gallery that really motivated me to make this post. Learning about remote and esoteric places is a hobby of mine, and I have fun collecting facts about tiny islands in faraway seas the way some people have fun collecting stamps or bottle caps. Seeing galleries like Chantal Steyn's elevate this to a whole new level, though, and make it clear how charged with wonder the universe really is. Out of thousands of miles of trackless ocean, far from the bustling harbors of Africa and South America and even from the glaciered shores of Antarctica, the powers that made the Earth saw fit to lift a tiny patch rock above the waves, and the result is simple, jaw-dropping beauty in every direction. What a world we live in.

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

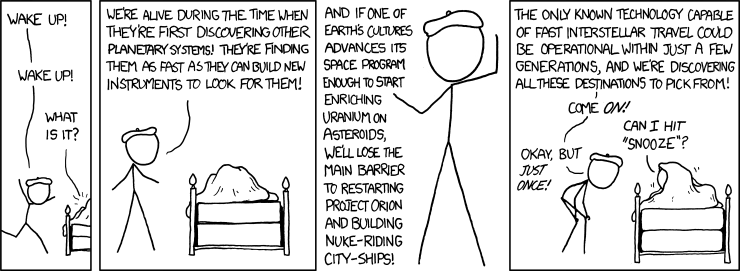

Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite

Last Friday NASA awarded a space science and engineering team lead by MIT $200 million to design, build, launch, and operate a spacecraft designed to better characterize the local population of transiting exoplanets. The mission, known as the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, hasn't yet begun, so Wikipedia's article is a bit terse, but you can still read more about its background and objectives here:

TESS

I missed the announcement (and an update here) because I was travelling that day, but this is wonderful news for the community of people who make a living finding planets across light-years of deep space, as well as those who are just happy that such a community exists. TESS was turned down in an earlier round of Explorer-class mission selections, which must have been a tough call given how much potential there is in this spacecraft. Unlike Kepler, which has spent the last four years staring at a narrow patch of space with no nearby stars, TESS will survey the entire sky with four wide-angle telescopes and 192 megapixels of imaging resolution, uncovering the closest, smallest tansiting exoplanets to Earth in the cosmos. Some of these will probably have life, and some of them may be serious targets for visiting spacecraft toward the end of this century or the next.

Most planets don't transit, since planetary orbits are essentially randomly inclined and only a fraction of a percent of exoplanet orbits cross a clean line of sight between Earth and starlight. There will surely be small, potentially earthlike planets "nearby" (as in tens of light-years distance rather than thousands) that go unnoticed by TESS, but the MIT team will find the close earthlike planets that transit sooner and cheaper than anyone else can. With missions like this in the pipeline, it's no wonder Randall Munroe's beret guy is so excited:

Monday, April 8, 2013

The Boston Molasses Flood

On January 15, 1919 a large molasses storage tank in the North End neighborhood of Boston failed, sending a wave of molasses into the city and nearby Boston Harbor. 21 people were killed and 150 injured in this bizarre event, which you can read more about here:

Boston Molasses Disaster

Fluids don't always do what you'd expect at strange scales. Molasses seems lethargic and harmless enough by the handful, but when a 50-foot-tall, 2.3 million gallon tank ruptured, the potential energy released had nowhere to go but the acceleration of a monster wave of dense but mobile fluid. The wave reached 35 miles per hour at its peak, and given its density buildings were demolished on contact.

Clearly this is totally unacceptable, and one of the first class-action lawsuits in Massachusetts history sought to ferret out the root cause of the failure. Partly it was a result of poor construction and inadequate testing. A rapid temperature increase over the previous 24 hours likely raised the tank's pressure more than designers anticipated. Finally, fatigue cracking, a poorly-understood topic considered esoteric at the time, probably immediately led to the catastrophic failure. It's one thing when failure happens while pushing the envelope of human achievement. Failure on an ordinary day at an ethanol production plant, by contrast, is just as tragic and totally uncool.

Saturday, April 6, 2013

Roger Ebert

Image credit (You really should go here first)

On Thursday evening Roger Ebert, a long-time film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times and one of the unofficial spiritual gurus of twitter, died after a decade-long battle with cancer of the thyroid and salivary glands. Ebert was a prolific and elegant writer, both on the subject of cinema during his day job and on the stuff of life in general on his blog. You can read more about his life and career here:

Roger Ebert

Ebert's life nearly ended seven years ago on an operating table (in his words he "came within a breath of death") after his carotid artery, weakened by neutron beam therapy and surgical scarring, burst. Fortunately Ebert was still in the hospital recovering from surgery at the time of the burst, and he eventually recovered, though he lost most of his mandible and his voice during the lifesaving artery reconstruction. After this he rarely appeared on camera again, and became much more active online, where he gained a tremendous following (myself included) on his blog and on twitter. Though his larynx was out of commission, his written voice was as lively as ever, and Ebert discussed interesting things across the gamut of human thought in an interesting way.

Generally I agreed with most of his opinions of movies, and found his thumbs-up or thumbs-down a reliable indicator of whether I would enjoy a film. That said, I think he completely missed the point of O Brother, Where Art Thou, and I don't understand what he enjoyed about Melancholia at all. Oh well. People are complicated and people are different.

So long, Mr. Ebert. You made Chicago and the internet brighter places while you were around.

Also: If you're confused about where the tags on this post came from, one is a reference to this recent piece Ebert posted on his Catholic upbringing and how it influenced his later views on philosophy, art, politics, and other whatnot. Insight!

On Thursday evening Roger Ebert, a long-time film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times and one of the unofficial spiritual gurus of twitter, died after a decade-long battle with cancer of the thyroid and salivary glands. Ebert was a prolific and elegant writer, both on the subject of cinema during his day job and on the stuff of life in general on his blog. You can read more about his life and career here:

Roger Ebert

Ebert's life nearly ended seven years ago on an operating table (in his words he "came within a breath of death") after his carotid artery, weakened by neutron beam therapy and surgical scarring, burst. Fortunately Ebert was still in the hospital recovering from surgery at the time of the burst, and he eventually recovered, though he lost most of his mandible and his voice during the lifesaving artery reconstruction. After this he rarely appeared on camera again, and became much more active online, where he gained a tremendous following (myself included) on his blog and on twitter. Though his larynx was out of commission, his written voice was as lively as ever, and Ebert discussed interesting things across the gamut of human thought in an interesting way.

Generally I agreed with most of his opinions of movies, and found his thumbs-up or thumbs-down a reliable indicator of whether I would enjoy a film. That said, I think he completely missed the point of O Brother, Where Art Thou, and I don't understand what he enjoyed about Melancholia at all. Oh well. People are complicated and people are different.

So long, Mr. Ebert. You made Chicago and the internet brighter places while you were around.

Also: If you're confused about where the tags on this post came from, one is a reference to this recent piece Ebert posted on his Catholic upbringing and how it influenced his later views on philosophy, art, politics, and other whatnot. Insight!

Thursday, April 4, 2013

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge

To be clear, this post isn't about the twin bridges between Tacoma and Gig Harbor, Washington on state route 16. Ten years before either of those bridges spanned Puget Sound, a single bridge over the Tacoma Narrows was completed in July 1940. The bridge was most famous for spectacularly and photogenically collapsing four months later, and you can read more about it here:

Tacoma Narrows Bridge (1940)

Text and photos aren't enough to convey the weirdness of how this structure behaved. Film captured between the bridge's construction and collapse shows it bucking and wobbling like a half-mile-long cartoon rubber band. It looks so impossible my mind refused to believe it was real when I saw the clips on Bill Nye the Science Guy back in the 1900s. It wasn't until my high school physics teacher solemnly described the aeroelastic resonance that brought down the bridge that I realized this really happened with a start:

Before World War II, aerodynamics was seldom considered when building large structures. For most buildings and bridges, this is acceptable since ground-based structures tend to be stiff relative to the wind forces they see. In this case, though, the winds of the the Tacoma Narrows were consistently harsh and the bridge deck was sufficiently compliant that the natural frequency of the main span wound up very close to the frequency at which a leeward vortex street was shed on blustery days. While the steel girders were strong enough to withstand jiggling like jell-o for a time, eventually fatigue cracks linked and the center span came crashing down.

The Pacific northwest has had some bad experiences with bridges. In addition to the Tacoma Narrows embarrassment, over the last 35 years not one but two floating bridges sank in western Washington, first in the Hood Canal and then in Lake Washington. Out of fears the 520 bridge between Seattle and Medina could suffer a similar fate, a billion-dollar effort is under way to replace it with a sturdier iteration as of the time of this writing. It's a shame Bill Nye couldn't have been of more help:

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

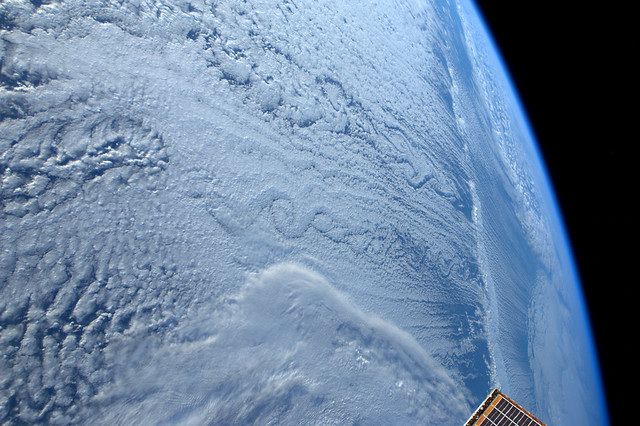

Von Karman Vortex Street

Image credit

When air flows around a blunt object at low speed it has an easy enough time splitting in two and flowing around the windward side, but linking back up on the leeward side is tricky. Often an instability results, and vorticies of opposing direction alternately curl and shed into the flow on either side of the obstruction. In the fluid dynamics world this is known as a von Karman vortex street, and you can read more about the physics and implications of this phenomenon here:

Karman vortex street

Theodore von Karman's name is almost ubiquitous on influential aerodynamics papers from the first half of the 20th Century. Since there's so much linked to von Karman's name already, I think adding his name to the phenomenon is unnecessary, but whatever, that's what the fluid physics community calls them. Vortex streets happen because air has a little bit of stickiness (more techincally viscosity), and because of this stickiness the faster flow on the sides of an obstruction tug on the decelerating air on the trailing side, sometimes gaining enough traction to yank it off and separate the flow completely. This creates a vortex that floats away on the wind.

Interestingly, while the dimensional and time scales of von Karman vortex shedding depend on the specifics of the size and shape of the object and the speed of the flow in which it's embedded, there's a remarkable space of possible vortex streets this allows. The streets can ripple from a bumblebee's wings or from mountain ranges, and can dissipate in a matter of milliseconds or endure for hours. Properly visualized in a wind tunnel or by cloud formations, it makes for a beautiful sight at the intersection of physics and instability either way.

When air flows around a blunt object at low speed it has an easy enough time splitting in two and flowing around the windward side, but linking back up on the leeward side is tricky. Often an instability results, and vorticies of opposing direction alternately curl and shed into the flow on either side of the obstruction. In the fluid dynamics world this is known as a von Karman vortex street, and you can read more about the physics and implications of this phenomenon here:

Karman vortex street

Theodore von Karman's name is almost ubiquitous on influential aerodynamics papers from the first half of the 20th Century. Since there's so much linked to von Karman's name already, I think adding his name to the phenomenon is unnecessary, but whatever, that's what the fluid physics community calls them. Vortex streets happen because air has a little bit of stickiness (more techincally viscosity), and because of this stickiness the faster flow on the sides of an obstruction tug on the decelerating air on the trailing side, sometimes gaining enough traction to yank it off and separate the flow completely. This creates a vortex that floats away on the wind.

Interestingly, while the dimensional and time scales of von Karman vortex shedding depend on the specifics of the size and shape of the object and the speed of the flow in which it's embedded, there's a remarkable space of possible vortex streets this allows. The streets can ripple from a bumblebee's wings or from mountain ranges, and can dissipate in a matter of milliseconds or endure for hours. Properly visualized in a wind tunnel or by cloud formations, it makes for a beautiful sight at the intersection of physics and instability either way.

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Prince Rupert's Drop

Drop molten glass into cold water, and the resulting object has some peculiar properties. The glass hardens into a tadpole-shaped blob with an immensely tough bulb, as in tough enough to survive a blow from a hammer without a dent. Nick the fragile tail, though, and a chain reaction explosively disassembles the glass in a matter of milliseconds. Such objects are called Prince Rupert's drops or Dutch tears, and you can read more about them at the Wikipedia link or just watching this exciting but sometimes-corny video from SmarterEveryDay instead:

The choice to goggle up turned out to be very wise on close examination of the high-speed video. It's startling how explosively the drop comes apart when the tail is disturbed. This isn't playing fast and loose with the language, by the way. The fracture front shoots through the drop at sonic speed, releasing a substantial amount of stored energy that disperses into the surrounding air on a supersonic shock front. This is a rigorous textbook definition of the word "explosion," in this case driven by internal stress in the glass.

There's more to materials science than strength. Many glasses have tremendously high strength, but very little toughness, meaning that they can be pulled on more than most metals before breaking, but can't handle impacts very well. This is why glass is never used as a structural material without the support of a tough resin or metal matrix (as in fiberglass parts), while metals can stand a beating bare without much trouble. Except for the tail effect, Prince Rupert's drops seem both strong and tough, something very exciting even if you ignore the pretty high-speed videos of glass explosions.

Monday, April 1, 2013

Peaceful Nuclear Explosion

During the Cold War the United States and the Soviet Union both seriously explored the idea of using nuclear explosives for excavation, construction, geological exploration, mineral extraction, and (of all things) firefighting. You can read more about that here:

Peaceful nuclear explosions

The American program was known as Operation Plowshare, an allusion to a passage from the book of Isaiah: "And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more." Apparently no one liked the name Operation Pruning Hook. As fitting as that excerpt may be, the Soviets didn't much care for Biblical allusions, and gave their program the rather anemic name Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy. In all, the Americans detonated 27 nuclear devices during Plowshare and the Soviets conducted 115 explosions in their program.

Both nations extensively studied the prospect of using the tremendous energy and power output of nuclear explosives to move lots of dirt very quickly. American nuclear scientists considered building a large artificial harbor in Alaska and cutting a second canal across Panama using thermonuclear bombs, but balked after the Storax Sedan proof-of-concept test (pictured) injected an unacceptably radioactive plume of steam and dust into the jet stream. Not to be deterred, the Soviets forged ahead and successfully created a large earthen dam on the Chagan River in Kazakhstan with the lip of a nuclear crater.

By 1973 the American program was effectively over, as excavation proved too polluting and efforts to stimulate natural gas production with nuclear shock waves disappointed expectations. The Soviets seem to have found more to their liking, since they continued using nuclear explosives to search for mineral deposits across Sibera and put out raging oil field fires until the wall-crumbling end of the Cold War in 1989. To be sure, nuclear contamination is nothing to sneeze at, but we'd be remiss to assume that the power of nuclear explosions is only the domain of the weapons designers. History shows that's just not true.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg/468px-Caspar_David_Friedrich_032_(The_wanderer_above_the_sea_of_fog).jpg)